THE SOBO OF

THE NIGER DELTA

A work dealing with the history and languages

of the people inhabiting the Sobo (Urhobo)

Division, Warri Province, Southern Nigeria,

and the geography of their land.

BY THE REVEREND JOHN WADDINGTON HUBBARD

M.A., CAMBRIDGE. B.SC. (Eng), LONDON.

FELLOW OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY,

RECTOR OF SOUTH WALSHAM, NORFOLK,

AND FORMERLY A MISSIONARY OF THE

CHURCH MISSIONARY SOCIETY,

IN WARII PROVINCE, SOUTHERN NIGERIA

WITH A FOREWORD

BY

HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR OF

SIERRA LEONE

SIR GEORGE BERESFORD STOOKE K.C.M.G

.

GASKIYA CORPORATION

ZARIA

INTRODUCTION

It is commonplace nowadays to hear the phrase "Changing Africa" in the mouths of those who have dealings with and are interested in the inhabitants of that great Continent. To others however who have no acquaintance with Africa the phrase can have but little meaning; for the belief persists, in spite of abundant evidence to the contrary, that the African will still continue in his old ways and in his old manner of life, no matter what Europeans can do in their attempt to introduce him to what has been called "Western Civilisation."

The profound truth of the phrase "Changing Africa" will however be borne in upon the minds of all those who have lived in tropical Africa even for a short time, and more particularly upon those who, like the writer, have lived in a country such as Southern Nigeria, which within the last forty years or so, has changed from being a country remote from Europe in every sense of the word, to one in intimate contact with that continent. We may therefore ask, of what does "Western Civilisation" consist, as viewed in such an apparently alien environment as Southern Nigeria? Probably the first impression of this somewhat mysterious entity is that of motor-cars, metalled roads, railways, canned groceries, smart two-storeyed houses, and the goods to which Manchester and Birmingham have given their names. Second impressions make it clear that besides these material things "Western Civilisation" consists also of good Government, a well-ordered system of education open to all young Africans, medical services of all kinds, and instruction in the Christian Religion. There are also less desirable things such as illicit alcohol, prostitution, and a lack of stability in the lives of many of the people due to the introduction of these new things; all of these however are recognised and are being dealt with both by the Government and Missions.

The writer worked for some years as a missionary of the Church Missionary Society (1) amongst a people who inhabit the Sobo Division, Ward Province, Nigeria, a remote tract of land in the north-westerly parts of the delta of the River Niger. These people are usually known to Europeans by the name "Sobo." We must however here anticipate what we say later in the text, and state that "Sobo" is a foreign Word, being an anglicised farm of the word "Urhobo", and that up till quite recently the people inhabiting the Sobo Division and neighbouring parts of other Divisions, who speak the Bini-type languages Urhobo, Isoko, Erohwa, Okpe and Evhro, had no community consciousness beyond that of the clan. To lump them all together and call them "Sobo" is therefore only admissible for the sake of convenience, and by way of contrasting, them. with their neighbours who speak Ijoh, Jeldri and Ibo; it is for these reasons alone that in this work we call them by this name. It must be realised that although the "Sobo" possess many customs in common, yet there is no such thing as the "Sobo tribe" or "Sobo nation." (2)

In these remote parts of the Niger Delta occupied by the people designated Sobo, "Western Civilisation" was making itself felt to a marked degree, and the writer was interested to observe how they reacted to it. In general he found that the older generation, considering it to be new-fangled and destructive of old ideas, regarded it with very grave suspicion indeed, whereas the younger generation, perceiving clearly its advantages, welcomed it with open arms. it may be understood that one result of this state of affairs is the formation of a definite line of cleavage between the old and the young amongst the Sobo. The former with their eyes in the past feel not only very much out of their depth in the new world opening out before them, but also very doubtful as to what the outcome of it all will be and what will be the future of their race; they tend therefore to become secretive and introspective. It is just the opposite with the younger people; with their eyes in the future and seeing

(1) This Society is usually known by its initials, C.M.S.

(2) Since the above was written, the word "Sobo" has largely gone out of use, its place being taken by "Urhobo." It is however convenient to retain the word "Sobo" designate the people in distinction to the language "Urhobo," spoken by some of them; see page 41.

visions of the glories "Western Civilisation" promises them, they are apt to despise and to do their best to forget the past of their race, which to them is so often summed up in one word—"bush." (1) It is of course obvious that these views, so prevalent among the younger generation not only of the Sobo but also of many other African peoples who have come into contact with the West, are but temporary phenomena; the time will come when "Western Civilisation" will be accepted as a commonplace and as the norm of everyday life; then saner views will prevail, and the Sobo will turn their eyes not only to the future but to the past also. Inevitably questions of their own origins and past history will arise in their minds, more particularly since they know of the history of European nations, which has all been carefully written down, and is now taught in schools. They will ask—have we no past? —what did our forefathers do? —where is the account of our history? —what are we to teach our children? They will then realise that these questions have been asked too late. Prior to the coming of the Europeans writing was unknown, and such knowledge of the past as there was, usually called "Clan Tradition," was in those days passed on from father to son, from mother to daughter, and was stored in the minds of the older generation. The question will then arise—where is the older generation who will tell us what we want to know? —and the answer, so plain to all, will be that they have passed away, and with them has died also all their clan tradition. Regret for the contemptuous attitude towards the past which they adopted when "Western Civilisation" was a new thing will then be unavailing remorse cannot bring back the past, and the Sobo will then have to face the fact that they are a people with an unknown past, and in so far as the future depends on the past, an uncertain future.

It is for the purpose of saving such heart-searchings that this work has been attempted, and the writer sincerely hopes that it will be of use in keeping in the minds of the younger generation of the Sobo the fact that their nation not only has a history, but a history of extraordinary interest and

(1) This is a word commonly used in Southern Nigeria to express not only the jungle, but everything primitive, savage, and uncivilised.

importance, first to themselves and then to neighbouring peoples, and that they form a and by no means unimportant part of the great Empire of Benin and of the British Empire.

The writer would point out that the work, as its sub-title says, deals "with the history and languages of the Sobo Division, Warri Province, Southern Nigeria, and the geography of their Land". That being so, the reader will look in vain for any account of the religion and customs of the Sobo; such matters are outside our province entirely, interesting and important though they be. It is as well to point out however that it has been impossible to avoid them altogether; history is not a water-tight compartment, religion and customs play their part in it; they have however only been referred to where to avoid doing so would have stultified the historical narrative. We give two examples of this. First, on pages 263 and following reference is made to the founding of the Adje Society in the Ewu and Uwheru clans and to the appearance of the edjorame (water-spirits) who were captured. The account is nevertheless given without any comment or attempt at an explanation, as this would take us outside our province. (1) The other example is this

(1) The writer is well aware that he is skirting and perhaps avoiding a very difficult subject indeed, when dealing with such matters as that referred to above; the water-spirit Eni of the Uzere Clan (see pages 218 and following); and other occasions when the super-natural world, the spiritual world, has apparently irrupted upon the natural world. An immense amount of discussion and argument has taken place as to whether beings alleged to exist in the spiritual world have also an objective existence in this, the natural world, or whether on the contrary they only exist in the minds of their votaries and worshippers; the writer will not be drawn into this discussion, as to do so would be an irrelevancy in a work of this kind. He will however say this; that whether Eni had an objective existence or not, the Uzere clan ordered their lives on the assumption that he had, and that if the edjorame, whose capture led to the formation of the Adje Society in the Ewu and Uwheru clans, were after all only aboriginal boys and girls at play in the water, the Society was founded on the implicit belief that the captives were visitants from the other world, and that any suggestion to the contrary would be scouted as absurd by members of the two clans concerned.

The writer also does not feel called upon to comment upon the use of "medicine such as is related on pages 207, and 213 and 214, except to say that it was expressly believed by those who used it, and by those who suffered from it, to have the powers ascribed to it.

in Chapter 29 we relate how Christianity was introduced to the Sobo, and in order to account for its rapid spread it has been necessary to give a brief account of the pre-Christian beliefs of the Sobo.

The writer must confess that he has been greatly tempted to depart from the subject which he set himself, and to discuss other aspects of the lives of the Sobo, more particularly their religion and customs. He realises however that these subjects, although connected intimately with history and origins, are yet separate, and are moreover so great in extent that if they were to be dealt with at all adequately, either a separate work would be required, or else this volume would be swollen to quite an unwieldy size. He has therefore in this respect kept rigidly to his subject.

In another respect however it has not been possible to keep rigidly to the subject, in that it has been necessary to include with Sobo history the history of certain other peoples who lie adjacent to them, but in other political Divisions, viz the Aboh, the Western Ijoh, and the Jekri-Sobo Divisions. The reason for this is that the boundaries of the Sobo Division are to some extent arbitrary, and thereby exclude peoples and clans who are intimately connected with the Sobo.

The work therefore deals with the geography of the Sobo Country and the history and origins of the people, the latter being traced from early days up to the coming of the Europeans in modern times; in other words so far as history is concerned, it deals only with what the Sobo nowadays are apt to regard as "pre-historic" times; when they were governed by the Ꜿba of Benin and not by either the Royal Niger Company or the British Government. The history of "modern times" is not dealt with, except in Chapter 29 when we relate how the Christian Religion came to Sobo-land. The work has been divided into five parts and five appendices. In Part I we give in a somewhat popular form an account of the geography of the Sobo country and touch upon the daily lives of the people. This part is intended to be read as an introduction to our theme, and is written more particularly for those who are not acquainted with the Sobo country. Those who know the country are advised to omit this part and to commence with Part II. In Part II we face the problem of ascertaining the history of a people such as the Sobo, who have been dubbed "primitive", and find out what facts we have at our disposal, so that we may give an orderly account of their history. Having in Part II ascertained our sources of information, we then in Part III see what legitimate deductions can be drawn from them, so that with their help we can see historical facts in their right perspective. In other words, Part II deals with facts, and Part III with deductions from these facts. We have thought it proper to separate the information in this way between Parts II and III, so that the reader may know what are facts, and what are the writer's deductions from those facts. With the former he feels confident that he will carry all his readers; with the latter this may possibly not be so, seeing that what appear to him to be reasonable and legitimate deductions may perhaps not appear so to others.

In Part IV we give the facts we have reviewed in Part II; it therefore constitutes an outline of the history of the Sobo and their immediate neighbours from early days up to the end of "pre-historic" times. This Part forms the main theme of the work, Parts I, II, and III, being introductory to it. In Part V we give an introduction to the phonetics and grammar of the Isoko language. In writing it we have assumed that the reader has some knowledge of phonetics; those not so equipped will be well advised to study an elementary book on the subject before reading Part V. This Part is followed by Appendix I in which we give some Isoko phrases in common use, and a small vocabulary. In Appendix II we study the causes and effects of the annual flooding of the Sobo Country, and make some suggestions for minimising the flood in certain parts of the country. This is followed by Appendices III, IV, and V, which are associated with Parts II and III. In them as well as in Appendix II and Parts III and V, it has been impossible to avoid the use of technical terms though we have used them as little as possible. The writer had hoped to include other matter dealing with the formation of sandbanks in the lower Niger and upper Forcados Rivers, but on his final return to England he found that his data were insufficient, and so the attempt had to be abandoned.

The reader will observe that in Parts XI and III we make use of information regarding the numbers of the population; kindly supplied to the writer by the Resident, Warri Providence, and which understand, were used in connection with the census of 1931; the reader will also observe that we draw from these figures various deductions as to conditions in the past. Owing to the fact of "Changing Africa" and more particularly of "rapidly changing Sobo-land," we would point out that if earlier and accurate figures, had been available, they would have been preferable to those of 1931; these latter have however been found entirely suitable for our purpose. Later figures will no doubt be taken with more accuracy than those of 1931, but it is not considered advisable to wait till they are available before proceeding with the work. The reason for this is that the years succeeding 1931 have seen such rapid changes in Sobo-land that. later figures would for this reason alone not be so suitable for our purpose as those of 1931. Parts II and III and their associated appendices, numbers III, IV, and V, are admittedly somewhat technical in places, and we call elementary mathematics to our aid, we therefore advise the non-technical reader, after reading Part I and perhaps Chapters 5 and 6 of Part II, to go straight to Part IV.

Throughout the work the writer has endeavoured to remember that he was writing not only for the reader equipped with a slight knowledge of mathematics and phonetics, but also for the ordinary non-technical reader and perhaps more particularly for the English-speaking Sabo. Technical terms and such use of mathematics as have been made have therefore been restricted to Parts III and V, and Appendices 1.1. to V; Part IV, the main part of the work, has been kept free of them. In view of the probability that certain readers will omit Part I and others Parts II and III, it has been found impossible to avoid certain repetitions in Parts I to IV; the writer therefore apologises for this to those who will read all four Parts. The work is illustrated, by photographs, maps, and diagrams from the writer's camera and pen.

The writer is most grateful to His Excellency the Governor of Sierra Leone, Sir George Beresford Stooke, K.C.M.G., formerly Chief Secretary to the Government of Nigeria, for so kindly writing the foreword to this work. He also wishes to thank most sincerely Mr. Cyril W. Dumpleton Member of Parliament for the St. Albans Division of Hertfordshire from 1945 to 1950, and formerly a member of the Parliamentary Labour Party's Colonial Committee, for his great interest in the work, and kind assistance in negotiations concerning its publication.

The writer also owes an immense debt of gratitude to his many friends who have given him such wonderfully kind and efficient help in the writing of this work. It is out of the question to record the names of all, as they are so many; it is fitting however to refer to three of his former colleagues. Most sincere thanks are due to the Rev. O. N. Garrard, now Rector of St. Cuthbert's, Bedford, for great encouragement given, and for help in constructing the map of the Sobo Division; to the Rev. J. M. Carr, formerly working for the Church. Missionary Society in the Sobo Division, for help in constructing the map; also to Dr. James Welch, B.B.C. Director of Religious Broadcasting during the recent war, and now Professor of Religious Studies at Ibadan University College, Nigeria; he it was who first inspired the writer to attempt this work, and gave him signal help and encouragement in its execution. The writer cannot attempt to mention by name all his Sobo, Ijaw and Abo friends, without whose efficient help this work would have been impossible; they are to be numbered if not in hundreds, at least in scores, and come from all strata in society, old and young, pagan and Christian, members of Odio societies, teachers and other agents of the Church Missionary Society, and many others; he thanks them sincerely one and all. He would like however especially to record his most grateful thanks to the following agents of the C.M.S. without whose hearty co-operation this work could not have been attempted: the Reverends Agori Iwe; B. P. Apena; S. O. Efeturi and G. D. Nabofa; Messrs M. Agbro, Avbaire, J. T. Ayibo, the late L Edeki, J. Edemete, J. Egwejemu, Esi Esedo, A. Ikogho, I. Loho, A. Obaro, D. N. Ockiya, P. J. Ojogu, J. O. Okoro, J. Owomue, E. H. Sapre-Obi, and N. Udoma. The writer also wishes to record his most grateful thanks to Miss M. M. Green and Miss B. Honikrnan, members of the staff of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, W.C.1. He owes them, a deep debt of gratitude for a careful study of the manuscript and for giving him most valuable advice as to the presentation of the material; the manner of presentation is however the writer's responsibility alone. He also wishes to record his sincere thanks to the following persons for kind help given. To the Resident, Warri Province, Nigeria, for supplying him with certain population statistics; to the Secretary of the Royal Geographical Society for allowing him to make use of a paper which the writer read before that Society on December 1st 1930, and: - which was published in the Geographical Journal of February 1931; to the editor of the International Review of Missions for allowing him to make use of an article he wrote for the April 1931 issue of that journal. He also wishes to thank the C.M.S. Bookshop, Lagos, Nigeria, for allowing him to make use of J. U. Egharevba's "A Short History of Benin"; and he is most grateful to his wife, and his two elder sons, John W. P. and Laurence A. Hubbard, for help in correcting the proofs.

As great confusion exists as to the spelling of Isoko and Urhobo words, we give at the end of this Introduction a table of the spellings which have been adopted in this work for certain proper nouns. The table is based upon popular usage, and gives the spelling employed, according as to whether the word applies to language, locality or people. We also give a list of the digraphs and special letters used in writing Isoko, Urhobo, and other languages spoken by the Sabo, together with the signs corresponding to them in phonetic script, and their meanings. For a fuller explanation the reader is referred to Part V.

As to bibliography, literature relevant to the subject of this work appears to be conspicuous by its absence. Some days spent in the Reading Room of the British Museum only brought to light H. Ling Roth's "Great Benin, its Customs, Art and Horrors" and certain articles in the Encyclopaedia Britannica as being at all relevant. These and Jacob U. Egharevba's "A Short History of Benin" are the only ones which have any bearing on the subject. From H. Ling Roth we have taken the quotation from Pereira's Esmeralda given on pages 145 and 146, for which we hereby acknowledge our grateful thanks. As regards J. U. Egharevba, this is published by the C.M.S. Bookshop, Lagos, Nigeria, and is an important work; the writer is greatly indebted to the author and has made considerable use of the material contained therein; the work is referred to in the text as "Egharevba."

In conclusion we send out this work in the sincere hope that it will fulfil the purpose for which it was written, and stimulate Sobo of the younger generation to value their past, and perhaps use the information contained herein as a framework on which to build up a full and complete history of their nation.

J. W. HUBBARD.

The Rectory,

South Walsham,

Norwich,

Norfolk.

Some pictures

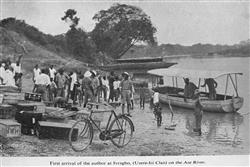

Unloading paraphernalia at Ivorogbo on the Asse River

5.426529366075872, 6.345275492874051

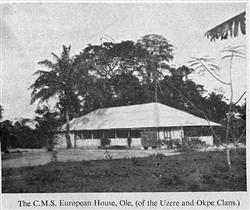

The C.M.S European House, Ole, (of the Uzere and Okpe Clans)

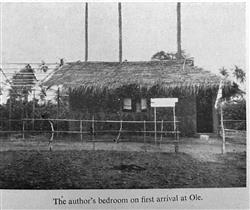

The author's bedroom on first arrival at Ole (Oleh)

Photographs of pages from the book.

Some I've placed on Flickr

More to scan / OCR

I've scanned the initial 4% of the book covering the introduction.

Work in progress!

Publication Date?

The book "History of the Urhobo People of Niger Delta" refers to The SOBO of the Niger Delta and puts a publication date of 1948.

Link

Link to a book that refers to "THE SOBO OF THE NIGER DELTA"

Uncle Jack does get a bit of a panning - he would have loved the argument!

Ꜿba

Uncle Jack uses phonetic letters in his book to pronounce place names, I've used a "Ꜿ". I'll refine this as I learn more.

The sound of this digraph is a very open "o", the same as "o" in "got".