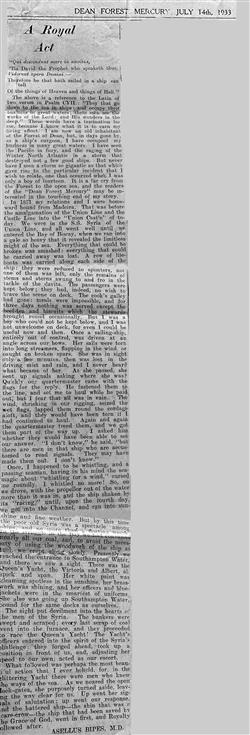

A Royal Act

"Qui descendunt mare in navibus,

'Tis David the Prophet who speaketh thus

Viderunt opera Domini:—

Therefore he that hath sailed in a ship can tell

Of the things of Heaven and things of Hell."

The above is a reference to the Latin of two verses in Psalm CVII.:

"They that go down to the sea in ships: and occupy their business in great waters; these men see the works of the Lord:

and His wonders in the deep." These words have a fascination for me, because I know what it is to earn my living afloat.

I am now an old inhabitant in the Forest of Dean, but, in days gone by, as a ship's surgeon, I have occupied my business in many great waters.

I have seen the Pacific in fury, and the raging of the Winter North Atlantic in a storm that destroyed not a few good ships. But never have I seen a storm so gigantic as that which gave rise to the particular incident that I wish to relate, one that occurred when I was only a boy of fourteen. It is a far cry from the Forest to the open sea, and the readers of the "Dean Forest Mercury" may be interested in the touching end of my story.

In 1871 my relations, and I, were homeward bound from Madeira. That was before the amalgamation of the Union Line and the Castle Line into the "Union Castle" of today. We were in the S.S. Syria of the Union Line, and all went well until we entered the Bay of Biscay, when we ran into a gale so heavy that it revealed the limitless might of the sea. Everything that could be broken was smashed: everything that could be carried away was lost. A row of lifeboats was carried each side of the ship: they were reduced to splinters, not one of them was left, only the remains of stems and sterns swung to and fro in the tackle of the davits. The passengers were kept below; they had, indeed, no wish to brave the scene on deck. The cook's galley had gone; meals were impossible, and for three days nothing was served except the beef-tea and biscuits which the stewards brought round occasionally.

But I was a boy who could not be kept below, and I was not unwelcome on deck, for even I could be useful now and then. Once a sailing-ship, entirely out of control, was driven at an angle across our bows. Her sails were torn into long streamers, flapping in the wind, or caught on broken spars. She was in sight only a few minutes, then was lost in the driving mist and rain, and I never heard what became of her. As she passed, she sent up signals asking where she was? Quickly our quartermaster came with the flags for the reply. He fastened them to the line, and set me to haul while he paid out, but I fear that all was in vain. The wind, shrieking in our rigging, seized the wet flags, lapped them round the cordage aloft, and they would have been torn if I had continued to haul. Again, and again the quartermaster freed them, and we got them part of the way up. I asked him whether they would have been able to see our answer. "I don't know," he said, "but there are men in that ship who are accustomed to read signals. They may have made them out. I don't know."

Once, I happened to be whistling, and a passing seaman, having in his mind the sea-magic about "whistling for a wind," cursed me roundly. I whistled no more! So, on we drove, with the propeller out of the water more than it was in, and the ship shaken by its "racing," until, upon the fourth day, we got into the Channel, and ran into sunshine and fine weather.

But by this time the poor old Syria was a spectacle among ships, and no more than a floating wreck. In the struggle in the Bay we had consumed nearly all our coal, and, to avoid the necessity of using the woodwork of the ship as fuel, we crept along slowly.

Presently we reached the entrance to Southampton Water, and there we saw a sight. There was the Queen's Yacht, the Victoria and Albert, all spick and span. Her white paint was gleaming, spotless in the sunshine, her brass work was shining, and her officers and bluejackets were in the smartest of uniforms. She also was going up Southampton Water, bound for the same docks as ourselves.

The sight put devilment into the hearts of the men of the Syria. The bunkers were swept and scraped; every last scrap of coal went into the furnace, and they proceeded to race the Queen's Yacht! The Yacht's officers entered into the spirit of the Syria's challenge: they forged ahead, took up a position in front of us, and, adjusting her speed to our own, acted as our escort.

What followed was perhaps the most beautiful action that I ever beheld, for, in the glittering Yacht there were men who knew the ways of the sea.As we neared the open dock-gates, she purposely turned aside, leaving the way clear for us. Up went her signals of salutation; up went our response, and the battered ship - the ship that was scare-crow - the ship that had been saved by the Royalty the Grace of God, went in first, and Royalty followed after.

ASELLUS BIPES M.D. [Arthur John Hubbard 1856 - 1935, enjoyed using nom de plumes.]

The above article is from the DEAN FOREST MERCURY, dated July 14th 1933.

The voyage from Madeira back to England was the return journey of Emma Hubbard (née Evans) and family after the burial of John Waddington Hubbard, Emma’s husband, who died 15th June 1871. He was buried in the old part of the English Cemetery, Funchal. Emma and the children, together with Emma’s brother Sebastian EVANS 1830 - 1909 had gone out to Madeira for his interment.