SOME CHURCH-BUILDING EXPERIMENTS

IN SOUTH INDIA

BY THE REV. G. E. HUBBARD, F.R.I.B.A, F.I.I.A.,

Corresponding Member of the Indian Institute of Architects.

From the October 1940 edition of the

JOURNAL OF THE INDIAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS

Page 55

Some Church Building Experiments in South India

The last ten years have seen the beginnings of a new movement with regard to church design in this country. Till quite recently the "Victorian Gothic" of the pioneer missionary, with its nasty icing-sugar pinnacles, its mouldings vulgarly carried out in plaster instead of honestly in stone and its general air of cheapness was the order of the day. Alas! it still is in many parts of the country, the Gothic arch being synonymous with Christian design.

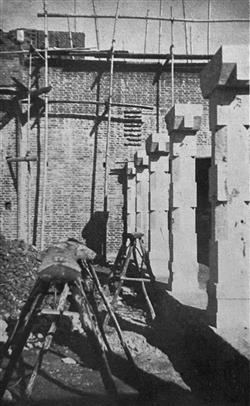

ARCHES AND SUPPORTING PILLAR, OYANGUDI CHURCH

One turns with relief to this new movement which has begun in church design. Expressed briefly, it is the intelligent use of indigenous design quite irrespective of creed. A criticism of the first exponents of this new venture was that they copied non-Christian places of worship much too closely instead of adapting indigenous architecture to the needs of Christian worship. Thus we find the Chapel of the Christu-Kula Ashram at Tirupattur, built in I932-33, looking uncommonly like a Hindu temple. In spite of this it is a step in the right direction, the aim of its builders being to make their Chapel and its worship as truly Indian as possible.

Rather better as an adaptation of indigenous architecture to Christian worship is the Chapel of the Social Centre for Women at Vellore, built by the American Arcot Mission. It is thoroughly Dravidian and follows the general style of a Hindu mandapam. Functionally too, its purpose is that of a mandapam adapted to Christian usage.

The new Cathedral of Dornakal, though hybrid in its design by the mixing of the Mohammedan dome with the Dravidian pillar, marks a big step forward and is a praiseworthy effort for the boldness and scale with which it has been conceived. The mixing of the styles was done deliberately to represent the blending of the non-Christian faiths in Christianity and to provide an edifice in which both Moslems and Hindus could teel at home alongside their Christian brethren.

In the very far south of India the "Victorian Gothic” point of view dies hard. It is still very strong and takes a great deal of dislodging. This is indeed unfortunate in a diocese like Tinnevelly which has the reputation of being the chief "Church-building" diocese in the whole of India. During the last two or three years it has been the writer's pleasure and interest to have built no less than five churches in the Tinnevelly diocese. Because of the strong prejudice against the use of architectural forms, other than "Victorian Gothic," in Christian places of worship, he has been obliged to resort to compromise (perhaps transition is a better word) to secure his ends.

Now the transitional buildings of France and England are always much more interesting than the purer examples of any particular style. They invariably denote the working out of new ideas instead of being exercises in an established vogue. So it will be, the writer ventures to think, in the case of these buildings of his illustrated with this article, in which the architecture of the pioneer missionary is being welded to the indigenous architecture of South India. Neither style is directly copied, at the same time the way is being paved towards a time in the not-too-distant future when pure indigenous forms will be the rule and not the exception or church-building in this country.

Oyangudi Church two years ago was a typical example of the pioneer missionary style. The original church displayed all the unsatisfactory features mentioned in the first paragraph. Its rebuilding is not yet complete but is sufficiently advanced for it to be seen that Dravidian pillars and arches of Indian form (horseshoe) take the place of the former "Victorian Gothic" elements. By this means the pillar and arch method of construction, so dear to the Tinnevelly congregations, is being maintained, at the same time indigenous forms are being introduced into entirely new settings. Everyone is satisfied and the congregation of this particular church are immensely proud of the appearance of their church which, they stoutly maintain, will serve as a model for all future churches in the district.

THE THEOLOGICAL COLLEGE CHAPEL OF TIRUMARAIYUR, NAZARETH

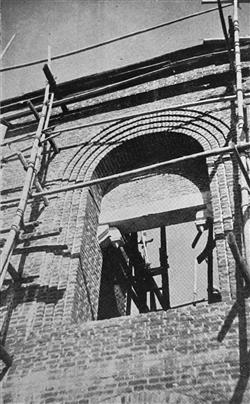

The Theological College Chapel of Tirumaraiyur, Nazareth, is a still further step in the process of welding "Victorian Gothic" with indigenous forms. Except for the steeply pitched roofs, it may fairly be claimed that Gothic has been eliminated. The steep roof, however, is a very definite feature of the architecture of the pioneer missionary and has therefore been retained in this "transitional" building. Many Dravidian features will be recognised by a study of the photographs, notably the courtyard, the pillars of typical Dravidian form, but with Christian emblems, and the brackets supporting the lintel beneath the arch.

As long as Christianity in this country clings to out-of-date European forms for its places of worship, so long will it be branded as something "foreign.” Surely the more common-sense method for its adherents and supporters would be for them to turn for inspiration to the magnificent places of worship which are part and parcel of India herself.

BRACKETS OF DRAVIDIAN FORM TO LINTEL WITHIN ARCH, TIRUMARAIYUR

The early Christians unhesitatingly borrowed from non-Christian Rome the external forms for their churches, why should twentieth century Christians in India, in a land of glorious and inspiring old buildings, do any less?

THE SOUTH COLONNADE, TIRUMARAIYUR,