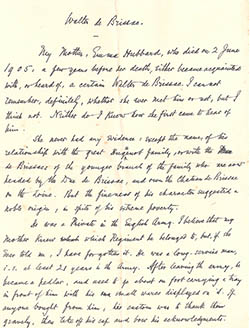

Walter de BRISSAC/BRISAC

My mother, Emma Hubbard (née EVANS) who died on 2 June 1905, a few years before her death, either became acquainted with, or heard of, a certain Walter de BRISSAC. I cannot remember, definitely, whether she ever met him or not, but I think not. Neither do I know how she first came to hear of him.

She never had any evidence, except the name, of his relationship with the great Huguenot family, or with the de BRISSACs of the younger branch of the family who are now headed by the Duc de Brissac and own the Chateau de Brissac on the Loire. But the fineness of his character suggested a noble origin, in spite of his extreme poverty.

He was a Private in the English Army. I believe that my mother knew which Regiment he belonged to, but, if she ever told me, I have forgotten it. He was a long-service man, i.e., at least 21 years in the army. After leaving the army, he became a pedlar, and used to go about on foot carrying a tray in front of him with his small wares displayed on it. If anyone bought from him, his custom was to thank them gravely, then take off his cap and bow his acknowledgments.

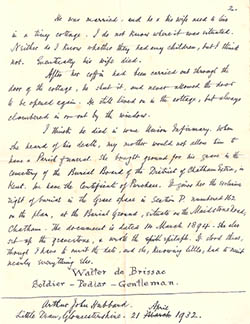

He was married, and he and his wife used to live in a tiny cottage. I do not know where it was situated. Neither do I know whether they had any children, but I think not.

Eventually his wife died.

After her coffin had been carried out through the door of the cottage, he shut it, and never allowed the door to be opened again. He still lived on in the cottage, but always clambered in or out by the window.

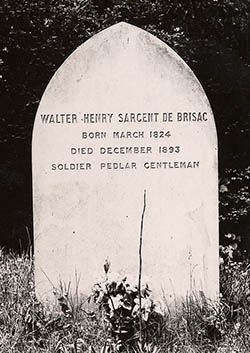

I think he died in some Union Infirmary. When she heard of his death, my mother would not allow him to have a Parish Funeral. She bought ground for his grave in the cemetery of the Burial Board of the District of Chatham Extra, in Kent. We have the Certificate of Purchase. It gives her the exclusive right of burial in the grave space in Section P. numbered 162 on the plan, at the burial Ground, situate on the Maidstone Road, Chatham. The document is dated 14 March 1894. She also set up the gravestone and wrote the epitaph. It stood thus, though I have to omit the date, and she, knowing little, had to omit nearly everything else.

Walter de Brissac

Soldier – Pedlar - Gentleman

Arthur John Hubbard

Little Dean, Gloucestershire. 21 April 1932

Correspondence

In August 2013 I (Judith F Hubbard) had correspondence with Catharina Clement, a local historian researching the background of Walter de Brisac of Chatham, in Kent.

Here are some key fragments of the correspondence:

• I had recently discovered from our records at the local archives (I work there) that Emma Hubbard paid for his burial and headstone to prevent a pauper's burial.

• No local link could be found to Emma Hubbard, but your web site has provided me with the tenuous link between her and the Walter Brissac lineage. It was always reported that this was a public subscription by local people to give him a good send off! This is another myth about Walter that has now been exploded.

• He was a very interesting character and although not directly linked to your branch of the family (maybe indirectly through his Huguenot descendance), I can understand why Emma, seeing this reported in the national press (Daily Telegraph) felt obliged to help a possible kinsman in his hour of need.

• I think I have traced his family tree back to Peter de Brissac, who came to England as a child probably with his father Benjamin de Brissac, a pastor from Châtellerault in France, in 1685. But I want to visit the Huguenot Society to try and confirm this last link.

• I have a lot of information on Walter and still finding out more about him. I am going to eventually publish his biography and perhaps this would be the easiest way to get you all the information.

• Unfortunately, the headstone is no longer there. The lease was generally held for 99 years on a plot and once the stones became unsafe, they were removed.

• The public subscription was just one of the many myths surrounding Walter Brisac/Brissac and has lent an aura of mystery to the character over the past century. My suspicions about a public subscription were aroused when I could find no newspaper article about it, which was strange given the coverage Walter was given on his death. It would be great to get the biography published this year, as it is the 120th anniversary of his death, but I think time will be against me. I still need to sort out his Huguenot connections and verify his family's Irish background.

• I have just acquired some copies of letters from Shropshire Archives, relating to the father of Walter (Douglas Pettiward Brisac) There is a copy of a letter included in one of his from his daughter Arabella Marshall Brisac (sister of Walter) to a Mrs Dickinson at Bramble House in Plumstead. (Frances de Brissac) She is asking for a favour (doesn't say what) as her mother is very ill and her parents have been married for 30 years. It would appear this must be part of a series of communications between Arabella & Mrs Dickinson, but the rest have not survived. This only because her father copied it into another letter.

It does suggest that the two families knew of each other (Walter's family lived at Bexley) and were probably aware they were distantly related along the Brissac line.

Transcription as follows:

Letter of 14th May 1847 copied into her father's correspondence:-

Madam,

I beg leave to communicate of Mamma's indisposition to you ever since the Bristol Riots, Papa sat up six weeks at the time with Mamma whose affliction is very trying, Papa is afflicted with chronic rheumatism. A favor which will be of infinite service to my Parents, thay have been married 30 years with honor & integrity. I have this honor to be {?}. (Unfortunately, the final word is difficult to make out.)

Your most obedient & honourable servant.

Arabella Marshall Brisac

To Mrs Dickinson, Bramble House, Plumstead.

Exploding the myth of Walter Brisac (Part 1)

The following appeared in Number 14 – Winter 2017

CHATHAM HISTORICAL SOCIETY Medway Chronicle

'Keeping Medway's History Alive' Exploding the myth of Walter Brisac (Part 1) by Catharina Clement

In 1893 the local newspapers reported the death of a pauper living at The Mount in Chatham. An inquest was subsequently held and revealed much about his background, which was published in the Chatham News and Chatham Observer. It would appear from these articles that the public took the death of this military ‘hero’ to heart and ensured he received a proper burial with a headstone. Purportedly a public subscription was raised for his gravestone.

Local newspaper accounts immediately following his death in December 1893 and more recent articles have all left this ‘gentleman’ shrouded in mystery. Who was the real Walter Brisac? Modern research tools have allowed us access to wider records than our predecessors could, but even these, paint a picture of a confusing nature. Walter sometimes set out to mislead, but on other occasions people misinterpreted his comments or put their own spin upon them to create an illusory character. At the time of his death in 1893 the national press reported that he was Dickens’ inspiration for Barnaby Rudge. This was immediately shot down as a myth by the journalist H.B., who correctly stated that this book was written in 1841; before Dickens could possibly have met Walter Brisac. A myth that is unfortunately still perpetuated today by some Dickensian authors! His military records seemed the first logical port of call, as it is known with certainty he was finally discharged from the army by the authorities at Chatham in 1853. He served in the 98th Foot Regiment.

According to these records he was simply Walter Brisac, aged 18½, a labourer born in St Mary’s parish (Anglican JFH) in Cork in Ireland. Walter enlisted in the army at London on 31st October 1843 for a bounty of £3 17s 6d. The description of him was:

Height: 5 foot 5 ¾ inches

Hair: light brown

Eyes: brown

Complexion: fresh

Marks: none.

Walter’s army career took him to Hong Kong in December 1844. S.M. Bard describes conditions in the colony at the time Walter served there. It was an ‘unhealthy place. The hot humid climate with swampy marshy valleys contributed much to this picture. Military dispatches reporting sickness in the garrison make sad reading. In 1842 Lieutenant General Gough wrote of the “destruction of the 98th Regiment [of Foot] by disease”, mortality among the troops due to “malignant fevers” had reached 39%. In 1844 it was described as “the melancholy return of death”, when 373 died out of the garrison of 1800, which is one death for every five men.’ This fever or disease was cholera, although the colony was also plagued with malaria and other tropical diseases. Hong Kong in the 1840s.

During late 1846 events became critical in India with threatened risings and so Walter’s regiment was transferred to that part of the world. ‘Initially the regiment was based in Calcutta (Kolkata) and Dinapore, however, in 1848 it moved to the Punjab where, although not directly engaged in the Second Anglo-Sikh War, a second battle honour — PUNJAB — was awarded. From here the regiment was one of the first British units to serve on the Northwest Frontier and spent between 1849–1851 in and around the Kohat Pass area. By 1851 the regiment had been abroad for a total of nine years and in that time it had suffered over 1,100 deaths, mostly from sickness, with almost 200 invalided home.’ The regiment appears to have returned to England in 1852. Walter was one of the fortunate ones, who had combated disease rather than warfare.

Having served in the army for about nine years he was invalided out on 23rd September 1852 due to ill health caused by sunstroke after serving in China and India. Brisac was of ‘exemplary character’ and awarded the Good Conduct Badge in 1848. Good Conduct Army Medal c. 1848 On his discharge, aged 30, he was to reside at New Peckham in Surrey.

Rumours had it locally that he was from a distinguished lineage and his father had disowned him. However his discharge address was that of his alleged father, Douglas Pettiward Brisac. Other information from this source of gossip does not correlate with his appearance, intellect and above connections. It would be highly improbable that as a labourer he was linked to a landed Irish lineage, as he frequently claimed to local inhabitants. More curious is the description by many who knew him as an educated and well read man. Charles Dickens found him an interesting character and had long conversations with him. Apparently he could speak several languages. None of this tallies with the education of a labourer nor does his very well formed signature on his army document.

A second document uncovered at the National Archives was purportedly the school records of a Walter Henry Sargent Brisac. According to this Greenwich School admission’s application the father was Douglas Pettiward Brisac. On reading this application it soon became evident that this was the one and same Walter Brisac, who had joined the army. One of the stipulations of entrance was that boys had to be very literate and would be asked at random at their interview to read a chapter from the bible. The boys were admitted aged 11 - 12 and were educated for three years before serving as naval apprentices, which took seven years. Walter was accepted at the school on 3rd April 1834 as a 1st class candidate. This group was reserved for children of commissioned officers. His father had to prove his naval qualifications to get a place for his son.

Douglas was a 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Marines, serving on HMS Bellerophon in 1813 and the 2nd battalion from 1814. It was also an expensive venture for the father as he had to provide a £50 bond, insuring his son would not go AWOL or misappropriate the equipment provided. You are asking at this point, why would a lad with a naval training have joined the army? All will be revealed later! This record does shed some interesting light on Walter’s family background. His father had to swear affidavits to both his own marriage and son’s baptism as he was unable to get hold of copies of the certificates from Ireland. Douglas Pettiward Brisac was married to Walter’s mother, Eliza Stapleton, at Holy Trinity Church in Cork on 7th January 1817. The affidavit he swore before a solicitor confirms that Walter was born on 24th April 1823 at St Finbarrs, Cork. ‘Ancestry’ has revealed a further child born in Ireland to this marriage in 1822, Arabella Marshall, and ‘family search’ has identified another three children, George Douglas (1818), Susan Catherine (1820) and Elizabeth Anna (1828), all baptised at Clifton in Gloucestershire. It would appear that the father’s naval career took him to Ireland for a brief spell, returning to Clifton near Bristol by 1828.

By 1834 the family were living at Bladenburgh cottage, Bexleyheath in Kent. The Bristol Riots of 1831 had forced the family to seek a safer environment to raise their children. From the above school record it is obvious Walter had only made a few subtle changes in his application for the army; date of birth out by a year, left out his middle names and distanced himself from an educated background by describing himself as a labourer. He also, however, declared he had never been apprenticed or enlisted in any other part of the military. Not quite true!

This is when a lucky chance upon a website led to the Shropshire archives and a series of letters held in the Haslewood collection between Lieutenant D.P. Brisac of Bexleyheath and Captain Joseph Jones of Bexley, covering the period 1844 -1847. A letter of 30th June 1845 from Lieutenant Brisac refers to ‘Walter Henry Largent Brisac absenting himself without leave on provocation since 26th October 1843’. The father states that he does not know where his son is, but that ‘he avail’d Himself of the Law being 21 years of age.’ By the time Walter’s father wrote this letter, the son would have been of age. But, under the terms of his admission to Greenwich School, Walter was required to stay in the naval service till he reached twenty one. On absenting himself in 1843 he had breached his father’s bond and by lying about his particulars he enlisted in the army just a few days later. Bizarrely his father had done the same in reverse. Douglas had joined Sandhurst as a cadet aged 17 in 1810 but was discharged just a year later by a friend. Yet not long afterwards he became a Royal Marine. Walter had to dissemble on his army papers to cover his absconding from the navy, however he was intelligent enough just to tweak the details and not tell outright lies. What the ‘provocation’ was to make him leave the navy is unstated, but later evidence may shed some light on this.

Walter’s mother, Eliza, died in early 1848 at Peckham where the family had just moved to their new home at 4 Dorset Terrace. It would have been some time before Walter would have heard the news, as he was serving in India at the time. Little more is known about the soldier till his military career ended.

Exploding the myth of Walter Brisac (Part 2)

The following appeared in Number 17 – Spring 2021

CHATHAM HISTORICAL SOCIETY Medway Chronicle

'Keeping Medway's History Alive' Exploding the myth of Walter Brisac (Part 1) by Catharina Clement

This instalment follows on from the article in issue no.14, which covered Walter Brisac’s early life and military career. Our current article focuses on Walter’s life after he left the army as well as his relationship with his family and his ancestral claims. He made certain claims that have since been proven to be untrue or at best tenuous.

During 1852 Walter Brisac was invalided out of the army at Dugshai in India due to ill health. He seems to have ended up at Fort Pitt Hospital in Chatham where a medical report was made on him on 29th June 1853:

‘Loss of health and weakness of intellect to be attributed to constitutional causes aggravated by climate; not the result of neglect, vice, or intemperance.’ ‘After examination I am of opinion that Walter Brisac is in consequence of weakness and injuries unfit for further service.’

By Walter’s own account to friends he suffered from sunstroke, although this does not seem likely to have caused any impairment to his intellect. Possibly he may have contracted some disease or ailment such as malaria that impacted on his overall health. He was paid an army allowance of 7d per day till 1853 when this abruptly ended.Correspondent and journalist, H.B. of Romford, interviewed Walter in the late 1870sand had access to a packet of papers he kept which he copied into various note books. The only known image of Walter Brisac was taken at the behest of this journalist by a studio photographer and reproduced in the Chatham News of 16th December 1893 along with his account of Walter’s life.

Walter was probably about 55 years old when this was taken.

Photograph of Walter Brissac c. 1878

Reproduced with permission of Medway Archives Centre

It is this journalist, who takes up the story of Walter’s efforts to gain financial redress from the records he had access to at the time.

‘Under date of August 28th 1856, is a portion of a letter from the Secretary and Registrar of the Royal Hospital, Chelsea, stating that the writer is “Directed to acquaint you that the Lords Commissioners have no authority under the regulations to grant any allowance from this establishment.”’

In 1867 Walter had tried them again for a pension and was again refused.

On his father’s death in 1868 he tried the Admiralty to see if he could qualify for a payment from them.

His last resort was a petition to the Secretary of War on 15th May 1873: ‘I have since my discharge done all I could to secure a living, but as age increases, I begin to find it exceedingly hard to earn my daily bread, and more especially everything is now so dear…praying you if it be possible to grant me some small allowance so that I may not be utterly destitute.

’Walter Brisac made other attempts to mitigate his financial hardship.

He applied to his father for assistance whilst he was still living in Peckham.

Douglas Pettiward Brisac replied to his son in the early 1850s: ‘I regret I cannot avail myself of coming to see you, being low in pocket’.

Although Douglas had come into an inheritance of £20 from his aunt Anne and was the sole beneficiary of his mother’s estate in 1838, he nevertheless often struggled financially. In the mid 1840s he sometimes had difficulty in feeding his family and by 1851 he was on half pay.

A correspondent (Old Dry-as-Dust) claimed in 1944 that Douglas died in poverty on a bed of straw and that Walter had refused his father’s pension, as that would have made him liable for his debts as well. This stands in stark contrast to the evidence of H.B., who indicates that Walter did pursue this angle and had made a fair copy of that letter.

In the end ‘Old’ Walter had to resort to obtaining a pedlar’s licence to maintain himself. Henry Smetham recollected in 1943 that Walter procured some of his wares from James Stevens; toilet soap, Dutch drops, pills etc. His main merchandise was haberdashery items. The only census that Walter can be traced on, that of 1881, described him as a haberdasher, aged 57. Apparently he was too much of a ‘gentleman’ to press his wares and so found it hard to earn his living that way.

Medway Union Workhouse, Chatham

Walter was so poor that about seven years before his death he was admitted into the workhouse by Doctor Buchanan on the point of starvation. However, he discharged himself from the workhouse a few months later, ‘considering himself superior to the other inmates’ and returned to his former way of life.

Despite allusions to the contrary Walter had a good relationship with his father. H.B. stated: ‘It has been said by those who claimed to speak with authority that the relations of the ragged recluse with his father had never been of an affectionate nature, that he was in fact an outcast from the parental home.’ The surviving correspondence for 18447 gives an account of a close family. Proof also comes from H.B., who had sight of Walter’s pathetic bundle of documents he kept tied up in string, which included letters from his father. A letter of 10th June 1853, just before Walter’s final discharge at Chatham, from his father read as follows:

‘Dear Walter,

I have received your dutiful letter this afternoon, hoping you remain in good health.

I shall be happy to see my Dear Boy if he can come to his Old Father’s address….Believe me my dear boy,

Your affectionate father

D.P.B.

P.S. Your sister sends her kind love to you.

A letter of a fortnight later was also concerned about ‘My Dear Son’s indisposition’ and thanked him for the present Walter had sent. This correspondence gives the impression of a family, who were on friendly terms with Walter in 1853.

The father and sister had moved to Morden Street in Rochester by the 1861 census. Douglas was by then retired from the Royal Marines, having suffered badly from rheumatism. From other local accounts it would seem that Walter was in contact with his father and Arabella Marshall in the early 1860s. His sister, a spinster, died aged 42 at Rochester and was buried in St Margaret’s Church on 18th December 1864. It seems probable that Walter would have attended his sister’s funeral. His father died four years later in October 1868. He wrote from his father’s address to the Admiralty on 23rd November 1868, just a month after his father’s demise, indicating that at this stage he was resident there. Walter also appears to have had detailed knowledge of his father’s financial affairs, suggesting a close connection at this point. There is little doubt from the facts uncovered that Douglas Pettiward Brisac was Walter’s father and Arabella the sister he often told people about.

Yet despite much truth about his parentage there were other tales Walter told local people about himself and his lineage that are not strictly true. He was not a lieutenant in the East India Company, never rising above the rank of private. His failure to advance in the ranks had nothing to do with his parentage or French descent. It can be ascertained from various records that the previous four generations had all been Captains or Lieutenants in the army or Royal Marines.

He was indeed descended from French Huguenots, but there is no trace of a landed Brisac Irish connection that can be found.

His grandfather was Lieutenant Walter Henry Brisac and grandmother Elizabeth Marshall.

A generation further back was his great grandfather Captain George Brisac, a director of the French Hospital in 1770, and his wife Mary Mortlock.

It was Walter’s great great grandfather, Peter Brisac, who fled France as a Huguenot child refugee. He came over from the Netherlands at the turn of the eighteenth century. Peter Brisac was naturalised by an Act of Parliament in 1708 and served in the British army as a Captain. He married Susanna Regnault, of French descent, in 1702, who ran a young ladies boarding school in Enfield, Middlesex.

This humble family of Huguenot extraction were always merely Brisac in England; perhaps Walter added the ‘De’ to his surname to give himself status when he was in straitened circumstances. Further research has uncovered the original Huguenot refugee as Pastor Benjamin De Brissac (Peter’s father) of Châtellerault in France. It would appear he arrived in the Netherlands in 1686, where he ministered in Amsterdam till his death in 1722. As a pastor with Calvinist views, his position in France became untenable after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685.

However, a curiosity in the family is the name Pettiward accorded to Walter’s father. Some Internet trawling came in useful here and it was discovered that a Reverend Roger Mortlock had changed his name by an Act of Parliament of 1749 to Pettiward on inheriting a substantial legacy from his uncle Roger Pettiward. From his will it can be ascertained that he was the brother of Mary Mortlock and so explains the names Walter’s father was given. This will of 1774 also left provision for a legacy of dividends and interest on £4,000 pounds worth of government securities to be paid to his brother-in-law George Brisac and his wife annually and upon their death the £4,000 to be divided equally among their surviving children. Whether this legacy found its way to George and Mary’s children is unclear.

It certainly never made its way down Walter’s line of descendants, as both Walter and his father are testimony to.

Strangely a Roger Pettiward, son of the above testator and of Finborough Hall in Suffolk, left a bequest to a George Brisac of £100 in his will of 1833. Presumably this was referring to his cousin, George Brisac junior of Cheltenham. This will was still in the process of being executed in 1864 as the identity of Lieutenant George Brisac of the Marines was unknown and so a notice was placed in the London Gazette of 28th June 1864, requesting any male heir or issue of George Brisac to get in contact within a month with the solicitors handling the case. Although George, then of Honfleur in France, did not die till 1836 he obviously was not aware of this inheritance nor apparently were his two grandsons, Anthony and George.

In 1865 a petition was made to the courts to settle this affair. The judge ruled that Roger Pettiward had actually meant Robert Pettiward Brisac, also a Lieutenant in the Marines and recent visitor to the deceased before he died, leaving him to inherit the legacy. A complete search and trawl through naval records and family history websites has found no trace of a Robert Pettiward Brisac or any other Brisac, who was a Lieutenant in the Marines in 1833, apart from Douglas Pettiward Brisac, suggesting they were one and the same person. Was this a misprint in the newspaper report or subterfuge on Walter’s father’s part? The legacy would probably have covered some of his debts but was hardly life changing. He certainly had sufficient knowledge of his uncle’s life to know that any heirs would be in France and unlikely to make a claim. It was not the first time he had pursued an inheritance when in debt, being quite proactive in chasing a legacy he felt was due to his wife in Ireland in the 1840s. Douglas made contact with distant relations when he was in dire straits at that time. Perhaps similar circumstances persuaded him to visit a dying relative, Roger Pettiward, in 1833 in the hope of being included in his will.

Finborough Hall in Suffolk

In later life Walter was aware of his family ties to Finborough Hall in Suffolk. H.B. notes there was correspondence between him and the manor house in 1869, following his father’s death. A letter from Finborough Hall stated: ‘I do not know of any money sent for your particular use,’ but advised he would contact his friend (a solicitor) in Chatham to delve into the subject of Walter’s father’s papers.

According to ‘Old DryasDust’s’ father, Colonel Pettiward was in residence at Finborough Hall at the time and he tried to persuade Walter to go and visit this relative, who had three daughters, and form ‘a marriage alliance with one of the ladies’. However by that date the wife of Roger Pettiward had died and there were no surviving offspring to inherit Finborough Hall. So there were no female relationsfor Walter to marry and inherit it. Walter was indeed related to one of the wealthiest families in England but gained nothing from this connection financially.

Another peculiarity was Walter’s alleged second middle name ‘Sargent’. There seems no ready explanation where this originated from. His sister, Arabella Marshall, was named after her paternal grandmother. This lead to much digging and beavering away at various sources to find that at one time the Brisac family had been tenants of a property owned by a Walter Largent in St Margaret’s, Rochester. In 1834 Susannah Largent, the widow of this Walter, left a bequest in her will to her sister Elizabeth (Marshall) Brisac. On checking back through the records completed by Douglas Pettiward Brisac for his son’s admission into Greenwich School it was clear that the middle name was Largent, not Sargent. A simple comparison of his handwriting with his own title ‘Lieutenant’ made this obvious.

This has been misinterpreted by even the keenest archivists at Kew and Shropshire. Some desire to carry on the Largent name inspired the Brisacs to continue this tradition as they had done with Pettiward.